a growing haggadah

A new edition of A Growing Haggadah (which is still available in its 2005 HTML version) has been printed. If you are interested in having a PDF version of the text to print and use (in whole or in part) at your Seder you can download it here.

- A Growing Haggadah (for family use)

- A Growing Haggadah (for a multifaith “model” seder)

- Experience A Growing Haggadah (in hypertext form)

Longer fallow periods seem to occur between editions of this Haggadah now. The previous edition is five years old, the preceding edition appeared three years before that. While I remain fairly satisfied, I am not complacent. I made many changes following Seder 5761 when Avigail and I visited Reed to see if she wanted to study there. The 2005 changes (though small) are significant, and were at her instigation. And now, Avigail mentioned at the end of Seder in 2009 that the time for a new edition had arrived and she wanted to help edit it. In recognition of her full participation in the task (both in writing, editing and making other, often structural, suggestions), her name appears on the cover.

Hurvitz’s Humanist Haggadah

This Haggadah is now a three-generation project. Its origin reaches back another generation. I brought from 3909 Burnside Ave., Los Angeles, the boxes Jay had labeled “Passover” and “Haggadah” home to Poway in 1989, a year after our return to California. In those boxes were Haggadot and other materials Dad had collected beginning in the early ’50s. Some of those tidbits found their way into this Haggadah, other materials are buds of ideas that may bloom in a different Haggadah. This text has moved on. Dad’s garden was extremely fertile; his presence still hovers over this Haggadah. Actually, it might never have existed were it not for the HHH (Hurvitz’s Humanist Haggadah). When I last skimmed that work (now many years back) I noticed little of it still apparent in this one (at this point, hardly even the Neertza, though I have restored some of the “bitterness” he experienced). Mom’s last typescript of Dad’s final edition is dated 1968.

Last year at this time I shared a button related to “Let My People Go” and the movement to free Soviet Jewry. This year, picking up from the struggle to free Soviet Jewry, I offer, first, a song from that movement that we sing at our Seder each year after Yachatz before the Maggid.

Фараону

Фараону, Фараону говорю

Отпусти народ мой

Фараону, Фараону говорю

Отпусти народ мой

Отпусти народ Еврейский

На Родину свою

Отпусти народ Еврейский

На Родину свою

Отпусти народ, отпусти народ

Отпусти народ домой.

Faraonu, Faraonu gavaryu; Ahtpusti narod moy. (2)

Ahtpusti narod Yevrayskee; Narodyenu svayu. (2)

Ahtpusti narod, ahtpusti narod, Ahtpusti narod damoy.To the Pharaoh I say: Let my people go! Let the Jewish people go to our homeland! Let the people, let the people, let the people go home.

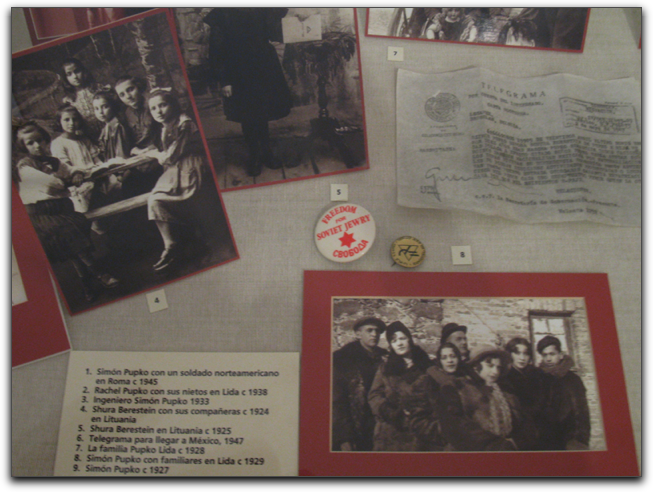

In December of 2008 Debbie and I were in Mexico City. There we visited the Jewish community’s museum where I was surprised to see a button I have in my collection:

There was no explanation of why this button from the American movement to free Soviet Jewry (with Russian text “СБОВДА” meaning “Freedom”) would be in the museum in Mexico City.

| Date: | ca. 1970s |

| Size: | 4.44 |

| Pin Form: | straight clasp |

| Print Method: | celluloid |

| {“type”:“block”,“srcClientIds”:[“fa6acb40-1814–494d-9561-f0f06e1ae5e2”],“srcRootClientId”:“”}Text | Freedom For Soviet Jewry СБОВДА |

water is scarce

I have increased the focus on water issues, especially at the end when we drink from Miriam’s Well. I know that other Haggadot suggest putting a “Miriam’s Cup” filled with water on the Seder Table. I prefer to…

drink from miriam’s well

A large pitcher of fresh, tasty drinking water from which all will drink at the end of the Seder stands on the table throughout the Seder. Also a bowl(s) to empty the remainder of wine in the cups before drinking from Miriam’s Well should be available.

I usually put slices of orange and sprigs of fresh mint at the bottom, fill the pitcher with ice, then fill the remainder of the space with cold water.Empty whatever wine remains in the wine glasses into the empty bowls then pour some water from the pitcher that has stood on the table into everyone’s wine glass.

We have escaped bondage and crossed the sea. We enter the arid land before us, made hesitant by generations of servitude—mixed with our recent struggle, and yet heady in our new freedom.

We have thirsted for freedom, but now we thirst for water. As with so many people in the world who do not have water, we face bitterness [Exodus 15:23] and quarreling.[Exodus 17:6–7, Numbers 20:11] Our ancient texts tell us that Moses was able to turn the bitter into sweetness and bring forth water. But many disputes over water remain.

Further, we are told that Miriam, the midwife of our liberation has stood ready, waiting to sustain us in the time ahead as we come to grips with our tasks and responsibilities.

Our Sages spoke of Miriam’s Well, created in the twilight of creation’s week. It now lies hidden in the sea of Galilee for Elijah to restore to us. Ishmael received water from it as “the well of living and seeing”; Rebecca drew from it when she greeted Eliezer; the well first appeared to our people when Moses struck the rock on Miriam’s account at the place of bitterness in Sinai—and it traveled with us throughout the desert years. Its waters, we are told, taste of old wine and new wine, of milk and of honey.

This is the well of the Ancestors of the world:

Abraham & Sarah, Isaac & Rebecca, Jacob & Leah and Rachel dug it;

the leaders of olden times have searched for it;

the heads of the people, the lawgivers of Israel, Moses, Aaron and Miriam, have caused it to flow with their staves.

In the desert we received it as a gift and thereafter it followed us on all our wanderings:

to lofty mountains and deep valleys.

Not until we came to the boundary of Moab did it disappear because we squandered our freedom by not fulfilling our responsibilities.

Now, as we begin a new season of renewal, may these cleansing, refreshing waters, reminiscent of Miriam’s well, recall for us a time of purity of purpose and help us focus on the tasks ahead.

All drink the water from Miriam’s well.

who is pharaoh?

I am not shy about mentioning human action in my Haggadah. In fact, I hope that the process of pursuing the Pesach adventure goads us to action. I write:

The classic Haggadah does not mention any human actors other than the nay-saying Pharaoh. The earliest texts that form the Haggadah were composed at the time of the beginnings of Christianity. Most scholars suggest that not mentioning human actors in the redemption stressed the power of God and diminished the possibility of imagining that Moses could be elevated to deity-like status. In our day, we are not so concerned and about deifying humans. In fact, the reverse is true, we need to enhance our understanding of ourselves as capable of transforming the world around us, and not wait for some force to appear to save us at the last moment.

Throughout the Haggadah I have marked questions for discussion related to this subject:

- Who can we name who dedicated their lives to the struggle for freedom?

- How did this happen? How did Moses move from oppressor to ally to liberator?

How do we move ourselves from passive to active? - What have I done to resist improper restraints?

- What new minor restrictions do I experience or see placed on others?

I am willing to ask how even we can become like Pharaoh:

We ask ourselves how we use our power to place other people in the narrow, limiting straits of “Mitzra’yim.”

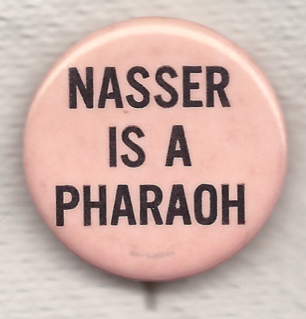

After all, we are told: In each and every generation an individual should look upon him or herself; as if he or she had left Egypt. And, so, it is not strange that different generations of our people have identified real rulers as Pharaoh (even if, within a generation his name might be all but forgotten!)

| Date: | ca. 1960s |

| Size: | 3.175 |

| Pin Form: | straight |

| Print Method: | celluloid |

| Text | NASSER IS A PHARAOH |

May all our pharaohs come to naught and be remembered as little as he. And, may we experience a liberating Pesach as we progress towards Shavuot.

your lapel buttons

Many people have lapel buttons. They may be attached to a favorite hat or jacket you no longer wear, or poked into a cork-board on your wall. If you have any laying around that you do not feel emotionally attached to, please let me know. I preserve these for the Jewish people. At some point they will all go to an appropriate museum. You can see all the buttons shared to date.

Chag Sameach

Each year I produce a illustrated calendar which we distribute free to members of the synagogue and some other synagogues and colleagues. The calendar is not sold.

I thought it might make an interesting page of illustrations to have some of your lapel badges as illustrations. Do you have them in a downloadable (presumably pdf?) form which I could use? I would of course give you as the source in the ‘credits and acknowledgements’ section.

I look forward to hearing from you

Todah meirosh

Rabbi Colin Eimer

Southgate & District Reform Synagogue

England.